- Home

- Tammy Bottner

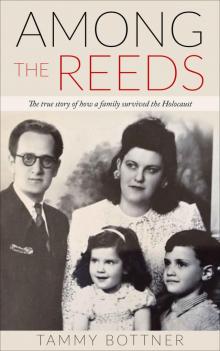

Among the Reeds

Among the Reeds Read online

Among the Reeds

The true story of how a family survived the Holocaust

Tammy Bottner

I dedicate this book to those who survived:

To my Dad, Al (Bobby) Bottner, and my Aunt Irene, whose childhoods were snatched from them too soon, and to Uncle Nathan, Aunt Shoshana, and Aunt Inge, for their remarkable resilience. And especially to my grandparents Melly and Genek, who had the courage to make unthinkable choices. The world can finally hear your story.

And also to the six million lost souls whose stories will never be told.

But when she could no longer hide him, she got a basket made of papyrus reeds and waterproofed it with tar and pitch. She put the baby in the basket and laid it among the reeds along the bank of the Nile River. - Exodus 2:3

Who has fully realized that history is not contained in thick books but lives in our very blood? - Carl Jung

Contents

Acknowledgments

Prologue

The Offner-Bottner Family Tree

Melly

Genek

Melly

A Wedding

Melly

German Occupation

Melly

The Anti-Jewish Laws

Melly

Andree Geulen and the Resistance

Melly

Bobby

Belgium and Holland

Melly

Bobby

Irene

Pictures

In Hiding

Back in Lvov

Genek’s Luck runs out

Melly

The Tide Turns

Liberation

Melly

After Liberation

Nathan’s Freedom

Melly

Reflections on a Calamity

Epilogue

Descendants of Leopold and Gertrude Offner

Sources and Further Reading

Further Holocaust Memoirs

Colophon

Acknowledgments

A huge thank you to everyone who encouraged and supported me through the process of researching and writing this book.

Thank you to Liesbeth Heenk at Amsterdam Publishers for your enthusiastic response to publishing this story, and to Luke Finley for your careful and thoughtful editing.

To my friends – thank you for cheering me on. I appreciate each of you tremendously. To my family, especially Sharon, who read early versions and provided helpful advice. Special thanks to my wonderful husband Danny, without whose support in writing and in life I would be lost. And to my kids, Ari and Sophia – it’s always for you.

Prologue

Tammy, Newburyport, Massachusetts

It was the spring of 1997, and I had a newborn baby. He had arrived ten days after his due date, pronounced healthy, and after four days at Newton Wellesley Hospital his father and I drove him home, me sitting beside him in the backseat because, like every new mother, I was worried he would stop breathing back there and who would know? But I only did that the one time, then I sat up front like a normal person, confident Ari would survive the car ride. I really was not an overly anxious new mother. As a pediatrician I had more experience than most new moms. I could see Ari was a strong and robust baby.

We had just moved into a little carriage house in Newburyport, and had fixed up the smallest bedroom as a nursery. Ari’s room held a light-colored wooden crib and changing table and a pretty lamp his aunt had painted for him, and sported a good-sized window which looked out onto a leafy street. Danny was working as a psychiatrist in a local practice, and I had four months’ leave before I would be starting work in a pediatric practice. We were newly settled in a lovely community. Everything was good.

Yet I was terrified. And I don’t mean just the regular “oh my God I have a newborn what do I do” type of terrified. I had already taken care of hundreds of newborn babies, many of them premature or sick. Feeding and caring for my sturdy little son was not difficult for me. My husband, Danny, was a bit scared in that way, but for me even the waking up at night to feed baby Ari was a cakewalk compared to the stress-filled, sleep-deprived years of my residency.

No, I was terrified because I was caught in a waking dream, that of a parallel universe, one in which I had given birth in a different time and place, in which an unspeakable horror was in store for me and for my child.

My grandparents were Holocaust survivors. My father, too, was a survivor. He had lived through World War Two as a young child in Europe. Despite the thousands of miles and more than fifty years of time separating my family's traumatic wartime experiences from that of Ari's birth, I found myself reliving the trauma. It was deeply troubling and very strange.

When I was a young girl, we would sometimes drive up to Montreal to visit my father’s parents, whom I called Boma and Saba. The adults would put my sister and me to bed and then stay up talking about “the war”. But of course I was still awake, and listening, and could hear all kinds of scary things. Since I wasn’t supposed to be listening, I never spoke about these late-night reminiscences. But the fear they elicited stayed deep inside me. I can’t even remember any specifics of what I heard now, but I can very clearly recall lying in bed with my heart pounding, experiencing equal parts guilt for not having had to suffer as they had, and horror at what they went through.

Decades later, while I was pregnant with Ari, Danny and I watched the Holocaust movie Schindler’s List. It was awful. Of course, I knew about the horrors of the Holocaust. I had read plenty of books, heard lots of stories, some even first hand. But this movie somehow clarified the degradation, the humiliation, the slavery, and the pointless sadism that the Jews endured under the Nazis. The movie struck a deep cord in me. For days afterward I couldn’t sleep, images of the movie haunting my imagination, a feeling of fear permeating my being so completely that I didn’t know what to do. But slowly I returned to normal, and I thought I had moved past the reaction the movie had caused me.

When Ari was born, however, those feelings came back. Even as I looked around my little house in beautiful Newburyport, part of me was living in Nazi-occupied Europe during World War Two. Profound terror shook me as I gazed at my baby boy lying in his bassinet beside me, and obsessive thoughts went through my mind – what if we were being hunted? What if boots were pounding up the stairs to our room? Where would I hide? What would I do if he cried? What if I had to give him up in order to save his life?

Was it just because of what I had heard as a child that I experienced this terrible distress? Maybe. But perhaps – and I mean this literally – the horror of the Holocaust was actually in my DNA.

Epigenetics is a relatively new scientific field, but a fascinating one. We used to believe that our genes, which we inherit from our parents at conception, formed a permanent and unchanging blueprint of our makeup for our entire lives. In other words, you got what you got, and that was it forever. We now know that it’s a lot more complicated. It seems to be true that genes themselves don’t change, but what is incredible is that there are countless ways that the expression of these genes is changeable. And almost everything we do, eat, or experience in life can change the way our genes are expressed.

So, it is possible that the trauma that my grandparents lived through, and that my father experienced as a child, actually changed their genes, and that these altered genes were passed on to me. If I inherited some of the trauma of the Holocaust in my very genes, maybe that explains my visceral reaction to seeing Schindler’s List and other Holocaust movies, and my overwhelming anxiety when Ari was born.

My family’s plight during World War Two was a story deeply rooted in my psyche. I thought a lot about it, and at the same time couldn’t bear to consider it. The whole thing was too terrible, too in

tense. In fact, for years I tried to avoid all things Holocaust-related once I realized that seeing movies or reading books about the subject elicited anxiety, sleeplessness, and a strange kind of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in me. It was only recently that I summoned the courage to interview my relatives and to fully imagine what they went through.

My father did not talk about his childhood experiences with my sister and me until we were adults. When he did finally divulge what had occurred, he insisted that he had previously told us, that we had already heard these stories. My guess is that his history was so prominent in his own psyche that he couldn’t imagine that we weren’t aware of it. I think of it like being in a loud concert hall, and having to explain to someone beside you that there is actually music playing. How could you not be aware?

As he got older my dad spoke more openly about his World War Two experiences. Once he retired, he spent about a decade giving regular talks to high-school students about the Holocaust, and about his story in particular. He felt, I think, that he was honoring the memories of those who were lost by giving these talks. Eventually, though, he too realized that the memories exacted a price: he found he was having nightmares and flashbacks after these lectures, and so he stopped.

But he wanted to tell his story. He thought about writing it down, but he is an engineer; his skills are more analytical than verbal and, while his English is excellent, still it is not his first language. The task seemed daunting. He spoke to me about hiring a ghostwriter. I started thinking that maybe I would do it. The more I considered it, the more I realized that I very much wanted to research what had happened and to put it together into a book. I felt very drawn to the tale; the story was mine as much as anyone’s.

This was not the first time a family member had mentioned the idea of writing down this incredible story. When I was in college, my grandmother Melly – Boma – mentioned that she would like to write a book about her life. As I recall, she thought for a moment and then said, you know, Tammeleh, I should tell you my story, and you should write the book. She had shared a few anecdotes with me, but there was a lot I didn’t know. Unfortunately, she passed away soon after, and I never had the opportunity to interview her and to obtain her complete story first hand. But her voice remained in my head, and as I embarked on creating this book I realized I had to tell at least some of it from her point of view. Sadly, it was also too late to interview my grandfather Genek; he too had passed away, years earlier.

Although I got a lot of information from my father, I realized it was important to interview as many other key players in the story as possible. In May 2016 I flew to Israel, and spent a wonderful week with my dad’s sister, my Aunt Irene, and her husband, Uncle Shlomo. I spoke to Irene at length about her memories, her parents, and her childhood. We pored over old photos and memorabilia, piecing together as much information as we could. I also visited my Great-Uncle Nathan. Still sharp as ever at eighty-eight, he astounded me with his remarkable memory for names, dates, and addresses. I talked to Nathan for hours, taping the conversation so I could review it later. Also I met with Inge’s son, my wonderful cousin Ami. Two of Ami’s own sons, Omri and Gilad, came to see me too; they all were eager to tell me what they knew about their mother’s and grandmother’s stories.

When I got back to the U.S. I started researching the many places where my family’s story had taken place. I studied about hidden children. I learned World War Two history. I ordered books, I read articles, I watched documentaries. But still, it was not possible to know everything that had happened seventy, even eighty years prior with complete accuracy. I knew the facts – where people were born, when they moved, where they lived. I learned the historic context. I could verify the major events that my relatives described. Whenever possible I verified the facts with my dad, or with my great-uncle Nathan, via Skype.

An additional challenge was that I discovered that many of my Jewish ancestors went by several different names. Known to the family by their Jewish name, they might be formally registered by a secular name, and perhaps referred to by most people by a nickname. For example, I found that my paternal great-grandfather Yehudah Bottner was registered in the Lvov phone book as Ignacy Bottner. My great-grandmother Beila sent a telegram signed Berta Bottner. My grandfather Genek was actually named Gimpel. And so on.

So I had a lot of information. But in order to write this book I had to take a few liberties. I had to imagine myself as my grandmother, as my grandfather, as my father, as each of the characters in the story, and to learn what they were likely thinking as best I could. Sometimes this was difficult, but mostly it wasn’t. I knew the characters well – as their older incarnations of course, but I did know them first hand. And the more I wrote, the more immersed I became in the story, the more I found that what had seemed to be odd, disjointed facts suddenly seemed to make more sense. Oh, I would think, that happened, and that must be why that other thing happened. And the timing of that makes sense, and that jibes with what was going on in that place at that time. At times I felt like a sleuth, piecing together bits of history with family anecdotes.

So how accurate is this book? So much of what occurred is lost, this long afterward. All the major occurrences happened in the way I describe, as told to me by family members. The historical parts of the book are true and verifiable. Much of the story is based on the memories of primary sources. Sometimes two relatives remember things a bit differently from each other, as is the way with memories. I have done my best to synthesize the information, and have added some plausible details that I have surmised are true, but do not know for sure. So my answer is that it is a true story, gleaned from first-hand accounts and from research. It is as accurate as I can realistically be, with just a dash of poetic license, and if I got some things wrong, I apologize. My intention is to recount a remarkable tale, to share that story with the world, and to preserve it for the future. To that end I have done the best I could.

The Offner-Bottner Family Tree

Melly

Germany, 1920s and 1930s

I was a disappointment to my father from the day I was born, September 30, 1921. My parents were in transit at the time of my birth, having fled from their native country, war-torn Poland, in the bloody wake of World War One. Mama and Papa, Gertrude and Leopold Offner, newlywed Jews, were searching for a better place to live. They headed into what was then a place of relative enlightenment, the neighboring country, Germany. Mama was already carrying me in her womb.

The year of my birth was one of transitions. I was born during a stopover when my mother went into labor just over the border in the German city of Leignitz. So I became a German citizen at birth. Years later Germany would strip me of this citizenship, of course – in Nazi Germany, Jews’ citizenship was taken away. In Nazi Germany, Jews’ everything was taken away. But that was later…

September 30 should have been a joyous day, when Leopold and Gertrude became new parents. But Leopold was not a happy man, and he was not pleased to hear he had a little girl; he wanted a son.

And maybe that early failure was imprinted on me, for hardship, disappointment, and heartbreak were to dog me, sadness to permeate my soul. It’s a fitting metaphor, I think, that my Jewish parents fled a difficult life to settle in Germany of all places. So things were not destined to turn out well. I’d have liked to have been born an optimist. It would be wonderful, I think, to have a sunny disposition, to see the world gently, view life as a cornucopia of opportunity. My sister Inge is like that, a sweet soul, God love her. But me, no. My motto is schver bitter leiben, it’s a hard and bitter life, because mostly that’s how it has been. But I was tough, born on the run, and destined to keep moving all my life. Fate dealt me some bad hands, but I fought back with all the grit and brains and determination I had in me.

My father Leopold was born on October 21, 1887, in Oświęcim, Poland – the town known in German as Auschwitz. Can you imagine? He was born in the town that would later house the most notorious killing

camp of the war. Fifty-six years later he would die there. I warned you that this was not a happy story. Leopold was the second of seven children, five boys, two girls. People had big families in those days. This was before antibiotics, before immunizations, in the days when a routine sore throat or a small cut could lead to overwhelming infection and death. People had a lot of children, but not all of them survived. Infant mortality was appallingly high.

My parents were both raised in Orthodox Jewish families. Things were different then: Jews and non-Jews didn’t mix much. Jews had their own neighborhoods, their own schools, their own stores. Men and women were more segregated too; each gender had prescribed roles, women keeping a kosher home, cooking, cleaning, sewing, and raising children, men working to make a living and studying and praying in synagogue as many hours as they possibly could. Everyone they knew spoke Yiddish, a colorful hybrid of German with a smattering of Hebrew, Aramaic, Latin, and Slavic roots, but written in the Hebrew alphabet. Jews had a hard life in Poland. Anti-Semitism was rampant, and pogroms regularly terrorized the Jewish community, as gangs of hoodlums took to the streets, looting businesses, and beating, even killing, any Jews they could find.

Among the Reeds

Among the Reeds