- Home

- Tammy Bottner

Among the Reeds Page 2

Among the Reeds Read online

Page 2

In 1914 World War One broke out across Europe, and my father was conscripted to serve in the Austrian army, as Poland was then part of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. Yes, my Orthodox Jewish father, later to be killed at Auschwitz, fought for the “other side” during World War One. Lots of Polish Jews fought during the Great War, defending the countries that would turn on them a couple of decades later. Jewish boys weren’t good for much in Poland, but they were tolerable as cannon fodder for the front lines.

I don’t know how much good a yeshivah boy would have been at fighting. Papa probably tried to keep his head down as much as possible. Jewish soldiers had double trouble. Not only did they have to slog through the mud, enduring the horror of trench warfare like everyone else, they also had to put up with the harassment of their anti-Semitic fellow troops. A lot of those Jewish soldiers were killed by their own side. It was a national pastime to harass the Jews, and in war conditions, with hunger and cold and depravity and guns – well, it doesn’t take much effort to imagine the terrible ends some of those kids came to.

But Leopold was a survivor. He realized his chances of coming out of the Great War alive were slim. If a French bullet didn’t take him out, if disease didn’t claim him, if gangrene didn’t set into his sodden feet, he might well be beaten to death by a fellow Pole. So he weighed his options.

In a bold and terrible move, he made a decision. He decided to instill poison drops into his eyes. I don’t know exactly what he used – he called the drops seedit or seedim. He told us years later that desperate soldiers knew how to get a hold of the stuff, and took their chances with blindness over certain death by cannon. He put those terrible poison drops into his own eyes. He must have suffered terribly, but the result was sufficient to obtain a medical discharge from the army. Papa wasn’t exactly blind after that, but he couldn’t see very well for the rest of his life. Like I said, he was a tough man.

And so Leopold survived the Great War, and in 1919 he and my mother Gertrude were married in Poland. They didn’t tell me details of their betrothal – parents didn’t discuss personal details with their children in my home – but I’m sure theirs must have been an arranged marriage. That was the custom. A shidduch, a matchmaker, would have gone between the families and made the arrangements. Marriage was a big deal, a mitzvah, a fulfillment of a promise to God to be fruitful and multiply.

Parents, especially fathers, made sure the young people were matched in various categories: how observant they were of Jewish traditions and customs, the economic status of their families, the education and potential of the man, the morality of the woman. There were financial considerations too – a dowry to negotiate, as well as wedding presents to get the young couple set up in their independent life. I wonder whether my parents ever spent an hour alone together before their wedding night. I doubt it. And that reminds me of my own marriage. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Jewish weddings were traditional, with a rabbi performing an ancient Hebrew service as the couple stood under the chuppah, or wedding canopy. Afterward, a party, but segregated by gender – men dancing with men, women doing the horah in an adjoining area, gossiping and giggling separately from the men.

I wonder how my mother felt about her groom. At age twenty-five she was relatively old to arrive at the chuppah, but the war had interrupted the normal flow of life, and all the eligible young men who survived had only just returned from the front. And so she embarked on married life with Leopold, a 32-year-old man hardened by war, partially blind, fiercely intelligent, ambitious, a survivor. Not an affectionate man, her new husband, but determined and strong, tall, stern, with eerie eyes in his shaved, well-shaped head.

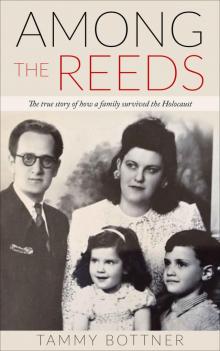

My mother, Gertrude Fischer, was lovely, with softly curling brown hair that she wore in a chignon, a small straight nose, and gray eyes. Like all Jewish girls, she was raised to be a balebusteh, a dedicated home-maker, keeping a tidy house, cooking for the family, and baking delicious pastries, cakes, and breads. On Fridays before Shabbos she worked tirelessly, scrubbing the floors, setting the table and preparing the chicken liver, matza ball soup, roast chicken, challah, and a platter of desserts.

Mama was the second of nine siblings, born in Sosnowietz, Poland, on October 28, 1894. Hers was a large and close family, and in fact, many of her brothers and sisters ended up leaving Poland around the same time my parents did, and settling near us in Germany. So I knew my Tantes and Onkels during my growing up years later. Because Mama was one of the eldest siblings, some of my Tantes were so close to me in age that I thought of them as cousins.

When I was still a baby Mama and Papa continued their journey, settling in the city of Chemnitz, where I grew up and where my siblings were eventually born, Inge in 1924 and Nathan – finally, a son! – in 1928.

Chemnitz was a big city at that time, with about three hundred thousand inhabitants. It is located in what would later be called East Germany, in Saxony, about fifty miles from Dresden. It was beautiful despite being a thriving industrial center. The buildings were ornate, with pointy roofs, and the Chemnitz River ran through town. The city boasted elegant plazas surrounded by gothic spires. The Ore Mountains were visible from upper balconies.

There was a thriving Jewish community in Chemnitz at that time, with about 2,400 Jews living in the city. My family was one of the typical Jewish transplants who had made their way there from Eastern Europe after the Great War. There were various Jewish organizations in town, Jewish schools, and even a mikvah. I remember there was a Jewish newspaper, the Jüdische Zeitung für Mittelsachsen, that my father would wait for eagerly every month. The Old Synagogue on Stephansplatz had been built before the turn of the century. It was an imposing Romanesque building with a cupola, enormous turrets, arched doorways, tiled roofs, and a gorgeous round window facing the street. It could hold 700 people. That famous synagogue was eventually destroyed, of course. It was attacked on Kristallnacht, on November 9, 1938, as were so many Jewish businesses in town. But that was much later.

Textiles had been produced in Chemnitz since the Middle Ages, and after the industrial revolution the area continued to be a center for spinning and production of various fabrics. Leopold was a businessman, and he chose to live in Chemnitz because it was a center for textile production. His company made gloves and socks, and I guess people needed a lot of gloves and socks during those years, because business was very good, and our family prospered.

Our first house in Chemnitz was at Glockenstrasse 2. This house was in downtown Chemnitz, on a lovely street of five-story attached homes, built of stone, and painted in warm colors, with balconies on the upper floors. But after a few years, as my family’s business prospered, we moved to a larger house.

As our finances improved, my family hired servants and a governess; we even acquired an automobile when I was a toddler. I know this because I remember falling out of that car once, when I was about two, and I have a scar as a souvenir. Later, when we were destitute, reminiscing about those years of plenty, they seemed like a fairy tale, a dream. I mean, to think we had the money to afford a car in Germany in 1923!

Not that my childhood was easy, or even pleasant. My father was extremely hard on me, and my mother was unable to protect me from his exacting standards, or from his wrath. Until my brother Nathan was born, Leopold insisted that I, his eldest daughter, shoulder the Jewish traditions he believed in so strongly. In addition to regular school, my father insisted that I study Hebrew and Torah like a boy. Personally, I never cared for religious life, but that was irrelevant. If I complained I was whipped.

Many Jews who emigrated to Germany around this time abandoned the Orthodox religion of their homeland, assimilating into the secular goyishe German society. The world was changing, and people were embracing a more modern way of life. Not so my father. Ironically, he became ever more observant as the years went by, almost fanatical. Maybe his mind was already starting to slip, his religiosity an early sign of the madness that was to come.

All I knew was that P

apa forced me to study like a boy, and I was terribly resentful of the burden he placed on me. I became the surrogate son – studying Torah – but also was forced to play the role of the perfect daughter, taking ballet lessons, and learning how to keep a home. My family was economically privileged, but I did not have the privilege of free time, or of free choice for that matter.

And while school came easily to me, and I was naturally gifted in cooking and baking, and loved to knit – I found knitting very soothing, and it gave me a creative outlet to design complicated patterns in my sweaters – I always felt awkward with the ballet lessons. I was not built like a ballerina, with my knock-knees and my pudgy thighs. But you see, I had no choice, so ballet it was.

When I was three years old my sister Inge was born. Despite loving my younger sister, I sometimes mistreated her, maybe taking out on her the resentment I was not allowed to express toward my father. Inge was a lovely soul, the gentlest of children. Despite that, I teased her mercilessly, telling her she wasn’t really part of the family, that our parents had found her on the street and adopted her. I told her the rest of us had blue eyes, and hers were brown, because she wasn’t related to us. Poor Inge was no match for my sharp tongue, and it is with shame that I admit I caused her terrible pain. When she ran off crying I felt no sorrow. Children’s cruelty can be astonishing.

During the years before the Nazis came to power, despite the tyranny at home, life was as normal for my family as it would ever be. My many aunts and uncles lived either in Chemnitz or nearby, and we had frequent visitors to our lovely new home at Postrasse 1, located west of downtown Chemnitz. This home was a free-standing house, different from the inner city attached home we had lived in previously. We had a leafy yard, and lovely views of the lush countryside. Still, I sort of missed living downtown so close to all the stores and cafes.

I remember so many Shabbos dinners around our grand dining table, the white tablecloth, the polished silver, and candles reflecting on Tante Rozel and Tante Anna’s bright eyes, Uncle Herman mischievously kicking my leg under the table, trying to get me in trouble. Inge smiling shyly at the guests in her sweet way.

I should mention that although my parents’ first language was Yiddish we spoke German at home. My father insisted his family be well educated, and the shtetl Yiddish was not to his liking. Our governess and tutors schooled my siblings and myself in the posh German of the upper classes. Little did I know that this linguistic ability would help save my life someday.

In 1928 my father’s dream of having a son was finally realized when Nathan was born. Nathan was Leopold’s darling child, and I was both relieved that a boy had arrived and resentful of the obvious favoritism he inspired. Nathan was a beautiful child, with big blue eyes, and as he got old enough, I recruited him in my persecution of poor Inge.

We were cruel to Inge as children are, but we really didn’t know how much we hurt her until later. I guess our constant teasing and taunts really did a number on her. One day when she was about nine years old, my mother found her standing on a kitchen stool with a belt around her neck. Inge was planning to hang herself! My mother’s screams still ring in my ears to this day. She managed to reach Inge in time, but the horror of what almost happened stayed with all of us for the rest of our lives. I was whipped for the part I played in making Inge miserable, further fueling my resentment against my father. But I really was sorry. I was more careful with Inge after that.

Most people aren’t even aware that another war took place between Russia and Poland after World War One ended. The Bolshevik Russians were trying to establish a communist regime in the area, while Poland was desperately fighting to stay independent. Fierce clashes took place between the Red Army and the Polish army, in a country already ravaged by the Great War. In the aftermath of World War One, Poland was a place of upheaval and uncertainty.

Desperate people like my parents streamed out of the area, heading west, into Germany and beyond, searching for a better life. Most of them came by foot or horse-drawn buggy, carrying sacks of belongings, destitute, with children alongside and babies strapped to their mothers’ backs. Some of these refugees were Jews from the towns my parents had grown up in.

My father became very involved in helping these Jewish refugees from Poland. By this time he was well established financially, and able to offer assistance to the desperate families that came through Chemnitz. I remember late-night meetings at my house, candles flickering, reflecting on the worry-lined faces of the men gathered in the back parlor, whispering frantically in Yiddish. I understood enough to realize there was danger in having these people here, although it was not my place to ask questions.

Sometimes the refugees stayed with us for a few days or weeks until they came up with a more permanent plan. My father acted as a liaison, made introductions, helped the men find employment. My mother fed and clothed the endless stream of impoverished Jews flowing through our home.

It was being involved with these refugees that made my father a suspect when the National Socialist party came into power in Germany in 1933. Hitler’s Nazis hated a lot of people, but in the early days of their power they especially hated communists. And housing and helping people from the Russian/Polish bloc brought my father under Nazi suspicion immediately. At least my father thought so; but Papa was becoming increasingly suspicious and strange. Maybe those poison drops he put in his eyes during the war did something to his brain, I don’t know. At any rate, it wasn’t clear to me at the time whether the Nazis really were observing us or whether that was a figment of Papa’s active imagination.

Like everyone, we were wary of the Nazi party, astonished that Hitler was being welcomed by the German people, but hoping that he would soon be ousted. Our adopted country was a civilized one, known for its music, its literature, its scholars. Hitler was an anomaly, a temporary madness; the German people would soon realize he was a madman, surely. Germany was much too cultured to harbor a leader who spouted hate, shouting and madly gesticulating and throwing his arm up in the air! Still, it was very upsetting to see his rallies attracting ever larger crowds. And soon his rhetoric scared the daylights out of me. The way he demonized us Jews, blaming us for Germany’s economic woes, painting us as thieves and villains. We had to hope that this madness was temporary.

I desperately hoped Papa was being paranoid, because having the Nazis scrutinize him, observing our family, seemed terrible, terrifying. The worst possible thing. Papa may well have been paranoid. But maybe that was the first of many pieces of bizarre luck, strange little fragments that came together like a macabre jigsaw puzzle, piecing our family's story together during those years of war.

As I said, I am not an optimist. But even I have to admit that some of the terrible things that happened to us may have saved our lives. It’s strange. At the time you have no idea. But later, looking back, you realize – if that hadn’t happened, and that hadn’t happened, maybe we wouldn’t have left, and if we hadn’t done that, and that, well…

At any rate, I will never forget the March morning in 1933, just weeks after the Nazis came to power in Germany, when Papa left home. Mama said he woke up that morning in a terrible state. He had dreamt that the S.R., the brown shirts, the most sinister of the Nazi soldiers, were coming for him. Mama tried to reason with him, saying it was only a dream. There was no rush, no reason to run off without a well thought-out plan. What was she to do? What about the house, the children, the servants? And the business? But Papa was adamant. The S.R. were coming, and he was leaving, immediately.

Papa packed a small satchel and disappeared toward the railway station. He was leaving Chemnitz, leaving Germany, taking the train to Holland. He would be in touch with Mama presently and we were to wait until we heard from him. We children, Mama, and the servants stood at the window and watched him walk down the street. I don’t remember what I felt. I expected him to be back in a couple of days, I suppose.

These S.R. stormtroopers Papa referred to, who seemed to have sprung up on

every street corner overnight, were indeed terrifying. With their shiny knee-high boots, brown-belted uniforms, and red armbands imprinted with the swastika, their goose-stepping marches around the city frightened everyone. We knew they hated communists and Jews, but we didn’t yet feel vulnerable. Our father was a successful businessman, and we were respected citizens in the community. It wasn’t until much later that we would realize the single-minded hate and brutality that the Nazis would direct toward our people.

Remember, this was March 1933. The Nazis had only come into power two months earlier. Most Jews, and non-Jews for that matter, were unhappy about Hitler’s rise, but not overly alarmed. Most people in our circle considered him a charlatan, an ignorant bumpkin, who would soon be exposed for the fool that he was and would disappear from public life. We had no way of knowing, no-one did, that he would become the all-powerful dictator of Germany; no-one could foresee the madness that was to come. In those early days one could easily leave the country; it was still the Weimar Republic, a fractured but democratic state. Even Jews could leave; in fact, as the Nazis slowly increased control of the country in the 1930s, Jews were encouraged to leave. The borders were open, trains were running, and people were coming and going. There were soldiers and stormtroopers around, yes, and they were starting to demand identification papers, but getting out was not a problem at all.

And so Papa left for Holland because he had a dream, a premonition, that he was in danger. We didn’t yet know it, but our privileged life as German citizens had just ended. I was eleven years old.

And just two or three days after Papa’s departure we awoke to hear a furious pounding at the front door. It was loud, shocking. Our home was a place of quiet voices, of restraint. I will never forget the two Nazi stormtroopers who stomped into the house demanding to see Leopold Offner. The soldiers were tall and imposing, and I remember my shock at hearing their crude German and disrespectful tone. I had never heard my mother addressed this way. Inge hid behind Mama’s skirts, whimpering, and Nathan flew into the governess’s arms. I stood by the stairs, partially hidden, watching as Mama explained that Herr Offner was not home, and that she didn’t expect him back for some time. The S.R. soldiers were enraged. They accused Mama of lying. Brandishing bayonets at the ends of their rifles, they stormed from room to room searching for Papa, tearing into closets, throwing our belongings on the floor, stabbing sofas and mattresses with their steely blades. Their boots left muddy prints on Mama’s beautiful rugs. By then we were all crying.

Among the Reeds

Among the Reeds